The quintessential survivor has died at 100. But her words will live forever - through us.

The passing this week of Holocaust survivor and cherished friend Judith Altmann at age 100 reminds us that we all now must bear witness.

Listen to the words of my friend, Holocaust survivor Judith Altmann, who survived a trifecta of terror: Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen AND the death marches, and lived to tell her story until yesterday, when she died at age 100.

Which begs the question, when a survivor dies, how can we enable her story to survive?

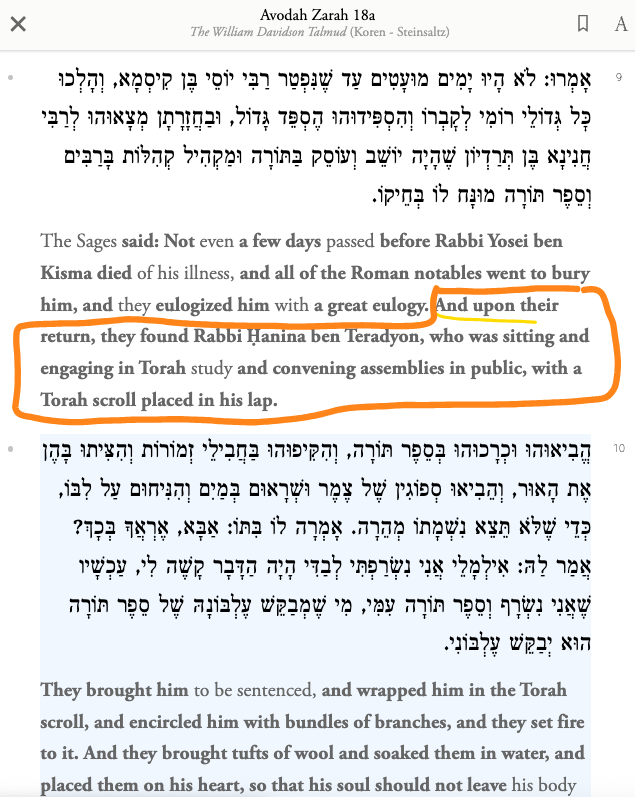

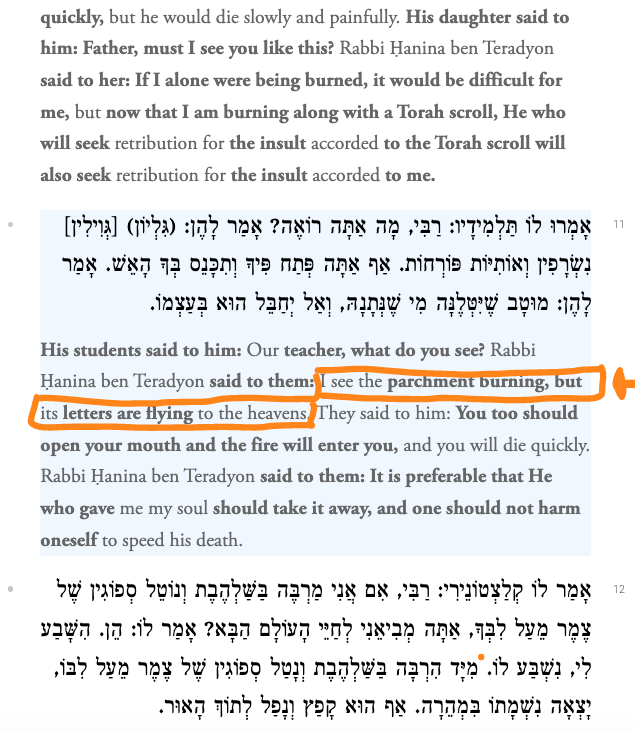

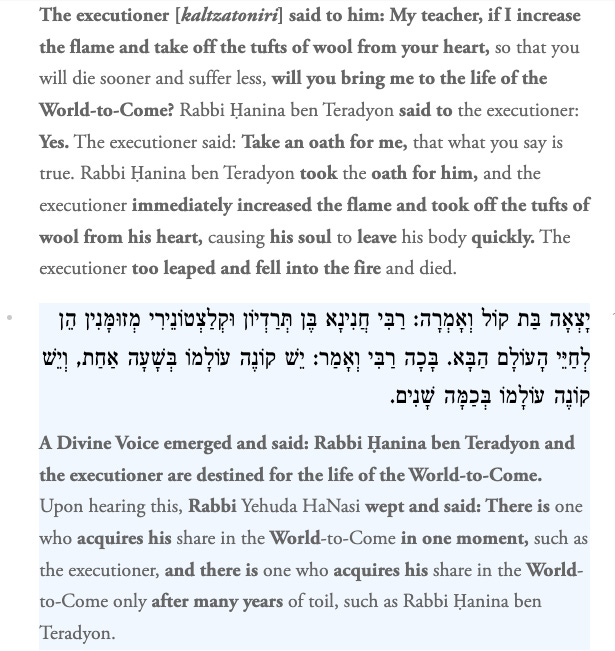

The Talmud tells the tale of Rabbi Hananyah Ben Teradyon1 who was arrested by the Roman authorities for the horrific crime of studying Torah in public. He was sentenced to be burned for that crime, and the authorities wrapped him in the Torah scroll, adding branches to fuel the fire and placing damp wool near his heart to prolong the suffering. As his life ebbed away, his students asked him what he saw.

“I see the parchment burning,” he replied, “but it’s letters are flying free.” 2

Judy Altmann’s flame has gone out, but her words will live on eternally. Her life’s work has been her story, and never once did she tire of that task. I’ve heard many survivors over the decades, and she was by far the most charismatic and engaging, which matters when dealing primarily with teens.

In 2010, I had the honor of accompanying Judy on the March of the Living, an annual gathering of Jewish youth in Poland. Our group of about 75 - mostly teens - adopted Judy as teacher, mentor, inspiration - and they protected her too. For this was her first time back at Auschwitz since she had been there during the war.

Here is part of her testimony that details her time at Auschwitz:

(I) was put into a line with other healthy, young people Mengele had selected for work. “We all had beautiful hair. They cut our hair, completely bald, and we were told to go a step further and we stood in front of a barrel. We were told to get undressed, completely naked. We were given a little, tiny piece of soap and in front of us it says ‘water.’ In our case, we went into a shower, but [in] our parents' case, they went into a gas chamber… and immediately to the crematorium.”

The entire camp was surrounded by barbed wire that was electrified, and if anyone tried to escape, they were shot immediately by guards armed with machine guns in the towers. Altmann was given a plain, gray dress and a pair of wooden shoes, and stood outside for many hours. She walked one hour from Auschwitz to Birkenau, where 1,400 women were placed in huge, low barracks. They slept in bunks that looked like bookshelves and the supervisor, who was also Jewish, told them not to make a sound. “Suddenly there is the most horrific smell… of burning. It’s choking,” Altmann said, recalling that she asked another Czech prisoner, who had been there for a few years, "'What is that horrible smell?' She said, ‘Oh these are your parents burning.’”

The prisoners were woken at 5 a.m. and made to stand roll call each day. “You stand there and Dr. Josef Mengele comes every other day and looks at the people that he already went through. If you are pale, he’ll take you out. If he sees two girls looking alike, like sisters, he will take one out, or a mother and daughter that he might have picked, he’ll take one out. He did not want to have any relatives together,” she recalled. “We stand on line for hours.”

They had been given no food and were afraid they would die of hunger. After the second day, they were given a little dish, so they could get a little soup in the evening. They received two ounces of water for the day. “It was a horrible place,” she said. Their greatest fear was that they would not make it back to the barracks from roll call.

Judy survived because she was young and could work, and also because she spoke six languages and was therefore useful to the Nazis.

Now imagine hearing that story being told by Judy, while standing in that very spot. After describing her ordeal in detail to the whole group, Judy took some of the teens into the same barracks where she had stayed. Birkenau is enormous, and much of it was destroyed as the Germans fled, but the women’s area was less disrupted and she found the place where she was held.

She remembered everything. And whatever might have been fuzzy before all came back to her on that day, including the spot where she had her final view of her parents (“We were marching to the left and they were marching to their death,” she said).

Then, as the actual March of the Living commenced, I noticed something peculiar.

She smiled.

And for the remainder of the march from Auschwitz to Birkenau, she did not stop smiling.

She did an interview with Polish TV.

She proudly held our New England placard.

She schmoozed with some of the 15,000 teens at this Jewish version of an Olympic village.

Judy looked extraordinarily…happy. Here? I don’t think I’m exaggerating in saying that her return to Auschwitz might actually have been one of the happiest days of her life, for she got the resoundingly clear message that not only will her people live on, but so will the story she spent most of her life telling.

We will remember. The next generation will remember. We will be your witnesses.

On the day following the visit to Auschwitz, our group left Krakow and rode all day, heading east, through the lush farmlands of Galicia, toward the Ukrainian border. As we rode along on a sunny, pleasant day, the grainy black and white photos from Hebrew School and History Channel documentaries suddenly gained color, thick forests took on a fairy tale hue, and the grass turned as green as could be. Poland is Europe's breadbasket, and I could see why. I could also see why the mystical threads of Judaism, Hasidism and Kabbalah, thrived here. Nature at its most natural, and most beautiful.

When we saw a horse pulling a plow, and I almost heard Tevye complaining about it. Yes we saw chickens, loads of chickens, and ducks and even a stork or two. We saw country folk aplenty. But what we did not see were Jews, in an area that was once was filled with Jews.

Throughout the ride, Judy continued to teach us about her own childhood village, a small town of about 15,000 just over the Carpathians from Galicia.

On that long bus ride, one of the students informed Judy that she wanted to “adopt” her story - that is, to take her life story as her own, and to become a witness in her place when she is no longer able to speak. I think we all took on that role during this trip. For Jews, that’s a true witness protection program – but we need to bear witness to more than just the horrors of the Holocaust.

We stopped for lunch in a quaint town called Lancut. The buildings in Poland hadn't impressed us too much - until we came here and visited one of the most beautiful synagogues I had ever set foot in. Small, colorful, filled with frescoed walls with simple but beautiful artwork and calligraphy. We danced and prayed. In the photo below, that’s Judy on the lower left corner, again smiling. In the photo below that, I stood on the elevated pulpit to lead an impromptu service. And below that, more dancing.

We sang and danced and prayed, and with the echoes ringing throughout the room, it sounded like many more than just our group were singing. We prayed Mah Tovu,3 which speaks of the beauty of this place of prayer, as we read its words painted over the entrance to the room.

Our singing sounded like we were accompanied by thousands of angels. It got so loud in fact, that a woman came in off the street and asked whether this was indeed a prayer service, intimating that it would be inappropriate for us to be celebrating at a time of national tragedy in Poland (the president had just been killed in a plane crash). Judy conversed with her in Polish, one of her six languages, assuring her that we were praying. She smiled and told Judy that in fact her mother had protected some Jews during the Shoah.

Judy later told me she did not believe it.

Our next stop, Belzec, was as difficult as Lancut had been enjoyable. Nothing remains of the infamous death camp, which was destroyed by the Nazis after it had completed its work of rendering Judenrein entire stretches of Poland and surrounding countries.

This was solely a death camp, not a labor camp. At least 434,000 Jews were killed systematically, brought on a single path directly to the death chambers, and only a few hundred remained alive at any time, only a handful of them surviving the war.

Then, as we began to say Kaddish for the victims, Judy told us that she had found a plaque memorializing her village, of Mikulince (all the Jewish communities that were sent to Belzec are memorialized at the site). This brought closure to one of the great unknowns of her family's life. If her village had all been brought here, as was now confirmed, this is where her sister died. Somewhere beneath the rubble were her ashes. She had never known this before. It was a cathartic moment for her, bringing her to tears.

Our group had bonded closely with Judy, so this became a tear-filled, cathartic moment for the teens as well. Many came up to comfort her. Some of us walked back to that spot and I photographed it for her.

We chanted the memorial prayer, so that now Judy's sister would be properly memorialized, at her own place of burial. We all felt fortunate to have helped her fulfill this quest, as painful as it was, and to achieve some closure.

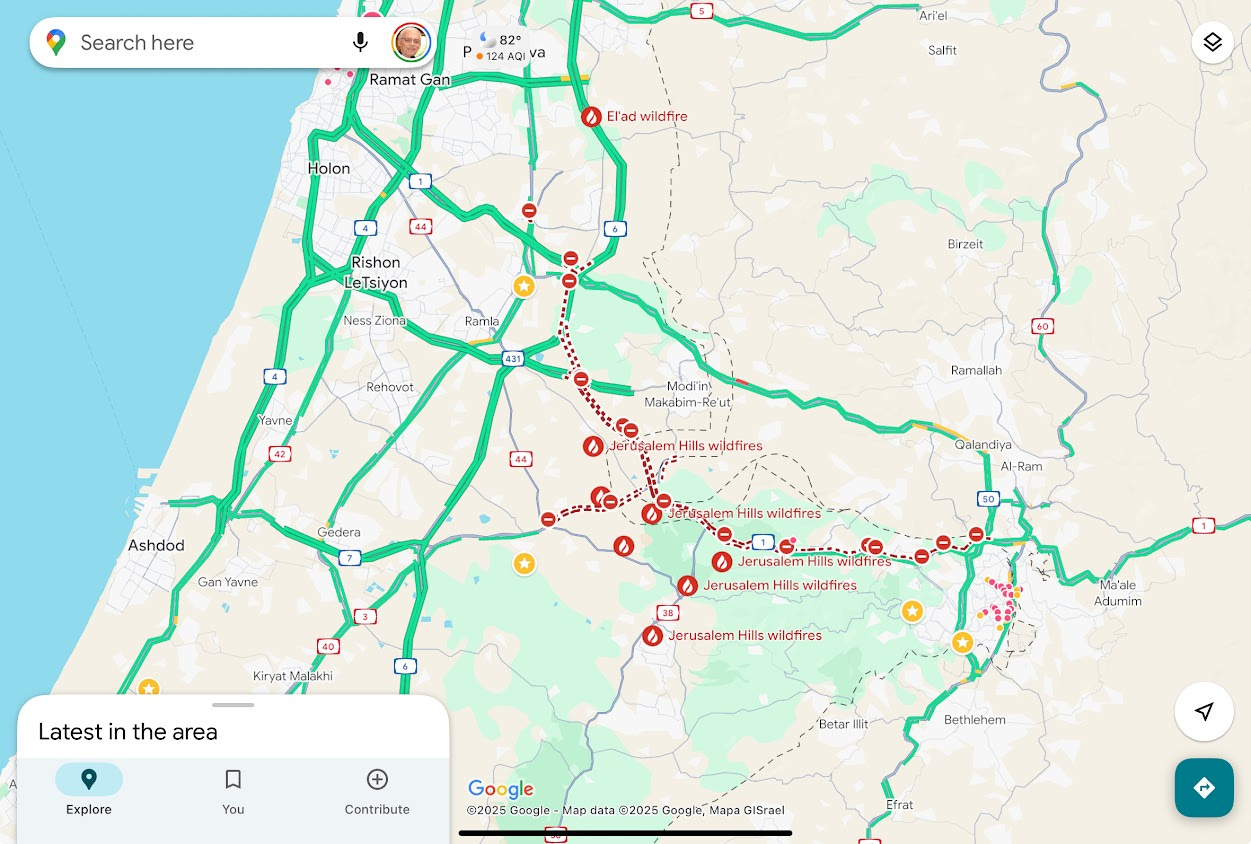

And so now one of the final witnesses to the Holocaust is gone.4 Judy died on Yom Hazikaron, Israel’s Memorial Day; a day when Israel experienced the worst wildfires in its history in the hills and forests near Jerusalem.

The question for us is how, as the parchment is burning - and the country too, and democracy - we can enable the sacred letters to fly free.

It is our responsibility to bear witness to the truth, no matter how uncomfortable that may be. And it is our responsibility, as a people who stands in Covenant, to open ourselves up to the flow of divine love and to bring light and blessing to the lives of others. That is what it means to bear witness.

When I led services in the synagogues of Poland with Judy and those teens, it was almost as if the dead were calling out to me. Europe is filled with dead synagogues. Beautiful, restored but still dead. Back in the 1930s, the chief rabbi of Krakow, who preached precisely where I stood, was firmly convinced that Polish Jewry was ascendant. “There… the Jewish people came into its own,” wrote Abraham Joshua Heschel of the Poland of that era. “It did not live like a guest in somebody else’s home, who must constantly keep in mind the ways and customs of the host. There Jews lived without reservation and without disguise, outside their homes no less than within them.”

At that time, Poland, not America or Palestine, is where the best and brightest studied Torah in glittering yeshivot, where three million Jews lived a vibrant life, separate from but unbothered by their neighbors. Poland was the great meeting place of Hasidic fervor of Galicia, the Talmudic expertise of Lithuania and the western scholarship of German Jewry. It all came together in 1930s Poland, arguably the most vibrant Jewish community in all of history.

The Jews of Poland must have thought it would last forever.

So as I stood there in front of our group at the Tempel Synagogue, a large ornate structure tucked between the narrow little alleyways of the Kazimierz, the Jewish quarter with no Jews, I speculated out loud with the teens what it meant to be a witness. I asked them to realize that, just as in their synagogues back home, the pews they were sitting in once belonged to someone sat in that same place, every Shabbat, every Rosh Hashanah and every Yom Kippur.

In the fall of 1942, the place we were in was full on Yom Kippur. And the next year, they were all gone, following the liquidation of the Krakow ghetto in March of 1943, a scene emblazoned in our consciousness by Steven Spielberg in the movie Schindler’s List.

And I asked the teens to think of that one individual while we said the mourner’s Kaddish. The person who sat in that pew. And at that moment we became living witnesses.

Witnesses don’t sit on their butts and listen passively while succumbing to a spiritual numbness. Spectators do that. Witnesses pray with intensity. Witnesses sing with fervor. Witnesses perform acts of selflessness and courage. Witnesses stand arm in arm with those who marched at the bridge in Selma and with those who suffered Egyptian slavery.

And witnesses dance.

And so we did.

Judy Altmann has finished her century-long race and has handed the torch to each of us. With the world aflame and evil ascendant, we have no choice but to grab hold of it with both hands. And now we, and the thousands whom she touched, must become her witnesses.

Here is the full story of the martyrdom of Rabbi Hanina Ben Tradyon, from the Talmud:

An interesting point is made by Dr Joshua Culp: The beginning of this story is fascinating for the contrast it offers between R. Yose b. Kisma and R. Hanina. The former is certainly a rabbi, assumedly one who studied Torah. Yet not only did the Romans not persecute him, they attend his burial and offer eulogies for him. Again, I am not reading this tale to try to determine what happened in actual history. I read it as an ideological statement. The author/editor of this story seems to be implying that one can be a rabbi and still get along with the Romans. R. Hanina was not simply a rabbi—he was provoking a fight. While we do have some sympathies for him, he is an ambiguous character.

Here’s my packet covering all dimensions of Mah Tovu - more than you will ever need to know about this prayer, which is traditionally recited upon entering the sanctuary.

Less than a quarter of a million Holocaust survivors are still alive, and most of them — 70% — will be dead within the next 10 years and 90% will die by 2040, according to a new demographic survey published today by the Claims Conference, reports eJewishPhilanthropy’s Judah Ari Gross.